Baseless Federal Investigations Would Stifle America’s Pioneering AI Industry Antitrust regulators distrust the artificial-intelligence market even at its most competitive. By JESSICA MELUGIN

Friedrich Hayek’s knowledge problem, handily summarized by Jeffrey Tucker as “the knowledge needed to run the social order is distributed in individual minds and inaccessible to planners”

Baseless Federal Investigations Would Stifle America’s Pioneering AI Industry

Antitrust regulators distrust the artificial-intelligence market even at its most competitive.

NATIONAL REVIEW

Jessica Melugin • 06/21/2024

Photo Credit: Getty

The Biden administration is going beyond antitrust enforcement in AI and is instead trying to predict the future of the industry itself. Reports indicate that the Department of Justice will open an investigation into AI chipmaker Nvidia and that the Federal Trade Commission will do the same for major AI investor Microsoft and ChatGPT maker OpenAI. This suggests that the agencies won’t be waiting for problems to occur before attempting to fix them.

We can’t say they didn’t warn us. FTC chairwoman Lina Khan recently told a Harvard Law School audience that regulatory intervention in the nascent AI industry is about “being able to issue-spot potential problems at the inception rather than years and years and years later, when problems are deeply baked in and much more difficult to rectify.” The DOJ’s assistant attorney general for the antitrust division, Jonathan Kanter, told the Financial Times that government intervention in “real time” is preferable because “the beauty of that is you can be less invasive.” Khan and Kanter sound a lot like the fictional regulators in R. W. Grant’s 1966 poem, “Tom Smith and His Incredible Bread Machine”:

The rule of law, in complex times,

Has proved itself deficient.

We much prefer the rule of men!

It’s vastly more efficient.

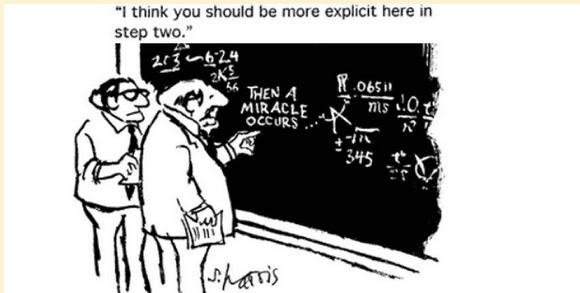

But the hitch in their giddyup, assured as regulators are that they can foretell the future accurately enough to ex ante regulate it, is that they can’t. No one, not even those with law degrees employed by regulatory agencies, can possibly predict the future of AI.

Friedrich Hayek’s knowledge problem, handily summarized by Jeffrey Tucker as “the knowledge needed to run the social order is distributed in individual minds and inaccessible to planners,” once again rears its inconvenient head. In this context, regulators cannot know if they are being less invasive.

U.S. antitrust authorities have an especially poor record of predicting the future when it comes to the technology sector. The merger of AOL and Time Warner in 2000, for example, underwent exhaustive review by two agencies and was eventually approved, after concessions were extracted, only to flop in the marketplace. By the time Microsoft’s antitrust trial ended in 2001, the browser wars that had sparked it had largely been reduced to irrelevance by the shift to mobile devices and the increased importance of online data and advertising. Even worse was the 13-year-long suit against IBM that ended in 1982 with the DOJ admitting that the case was “without merit.” Similar division-of-labor deal between the agencies in 2019 eventually resulted in antitrust cases against Google, Amazon, Apple, and Meta.

Trying to keep up with or predict the future of the tech industry won’t go any better for regulators this time around. Chipmaker Nvidia, founded in 1993 over a meal at a Denny’s restaurant, got lucky when its graphics-processing units, designed for processing video-game graphics, turned out to work well for the computational heavy lifting integral to training and operating large AI models. Nvidia’s stock price has gone from $15 per share in November 2022 to $121 at the time of this writing, and the firm now boasts a market cap of more than $3 trillion. (Cha-ching!)

But rather than seeing the meteoric rise of Nvidia as proof of an economic sector that’s competitive and open to emerging market leaders, Kanter pledged to move “with urgency” to investigate the company. He said that even though he thinks the nascent AI industry is “at the high-water mark of competition” right now, his agency must investigate.

Acting preemptively against a specific company in a market Kanter admits is competitive is a curious use of scarce regulatory resources. The DOJ’s and FTC’s preemptive approach, coupled with their ongoing cases against established industry leaders like Meta, Apple, Google, and Amazon, means that, as a practical matter, antitrust regulators now believe they can scrutinize U.S. firms even in markets that are competitive and are in no danger of ceasing to be. This attitude is reminiscent of another stanza in “Bread Machine”:

You must compete. But not too much,

For if you do, you see,

Then the market would be yours

And that’s monopoly!”

Read the full article at National Review.