“Have CEOs really gone quiet on climate change?”, by Simon Mundy, Financial Times

Some might see Hollub’s ordeal as fresh evidence chief executives should avoid saying anything in public about climate change, not to mention similarly charged issues such as diversity and inclusion

“Have CEOs really gone quiet on climate change?”, by Simon Mundy, Financial Times

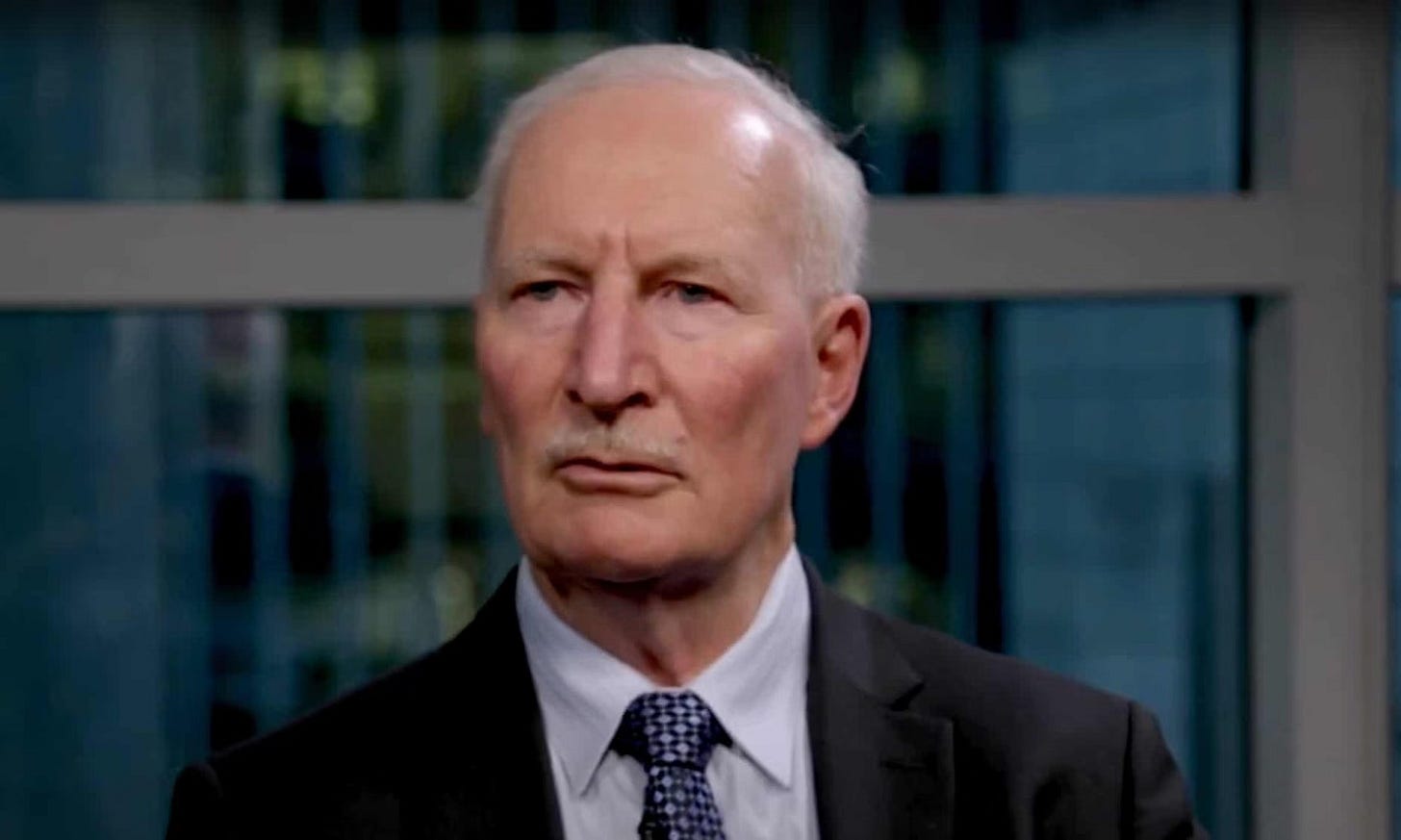

During a packed schedule of events last week in New York around climate action and international development, one of the most powerful speeches came from Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the UN climate change programme.

Clean energy investment was surging, Stiell noted, with the world on course for more than $500bn of investment this year in solar power alone.

Yet the bulk of that money is flowing to projects in the largest economies — including wealthy ones such as the US, as well as developing nation powerhouses such as India. Vast numbers of people in many other developing countries are still seeing little benefit from the green investment boom.

“If more developing economies don’t see much more of this growing deluge of climate investment, we will quickly entrench a dangerous two-speed global transition,” Stiell warned.

Broadening the reach of the global energy transition, while boosting its pace, will be a key focus of intergovernmental talks at November’s COP29 climate summit in Azerbaijan, where international climate finance will be top of the agenda.

Serious progress on these issues will need plenty of government support, but also heavy involvement from the private sector. No wonder, then, that many are concerned about what they see as flagging interest in climate issues from corporate leaders. But as we highlight in today’s edition, while many chief executives have indeed become quieter on these topics, it’s worth keeping this in perspective.

SUSTAINABILITY

Executives ride the sustainability rollercoaster

Vicki Hollub cannot have been totally unprepared for her experience at Climate Week NYC last week, but that won’t have made it any less mortifying.

Hollub, chief executive of US oil group Occidental Petroleum, had just taken the stage at a New York Times event when a group of protesters stormed it with banners accusing her of trying to deceive the public over her company’s role in the energy transition.

“Tricky Vicki, you can’t hide; we charge you with ecocide,” they chanted, before being bundled away by police.

“I feel bad that they have nothing better to do with their time,” Hollub said when she finally resumed her interview, in which she talked about Occidental’s plan to use carbon capture technology to reduce the climate impact of its oil and gas production.

Some might see Hollub’s ordeal as fresh evidence that chief executives should avoid saying anything in public about climate change, not to mention similarly charged issues such as diversity and inclusion.

Those who do are liable to be attacked from the right as “woke capitalists”, and from the left for trying to launder their image through “greenwashing”. Why bother?

There has been a lot of talk over the past year or two about “greenhushing”: companies, and especially their top executives, going silent on anything that has a whiff of sustainability. But the data suggests that this phenomenon, while real, is limited.

I got an exclusive early look at the latest research from two firms that have been tracking chief executives’ discussions of green and social topics in their calls with analysts. Germany-based IoT Analytics has analysed more than 95,000 earnings calls from 6,300 US-listed companies.

Chief executives mentioned the word “sustainability” in 7.4 per cent of those calls in the first quarter of 2019. That figure reached a peak of 26.6 per cent in the first quarter of 2022. In the third quarter of this year (as of September 27) it was 19.3 per cent — down from the peak, but still far higher than at the start of the study.

The mention rate for the word “emissions” showed a similar pattern. It rose from 6.7 per cent in the first quarter of 2019 to a high of 17.6 per cent in the first three months of 2022, before falling to 11.1 per cent in the latest quarter.

Data from US-based AlphaSense corroborates the broad trend. Tracking US-listed company earnings calls, it identified 845 mentions of “sustainability”, “environmental, social and governance” or “diversity, equity and inclusion” (or their acronyms) in the first quarter of 2018. That reached a peak of 3,650 in the second quarter of 2021, before declining to 2,151 between July 1 and September 27 this year.

So even in the US, where perceptions of corporate green backsliding have been strongest, the idea that chief executives have simply stopped mentioning these issues is clearly off. Despite the political backlash, they’re still talking about them on analyst calls far more than they did five years ago.

These numbers will still look alarming to some readers. If the global energy transition were truly getting on track, one might think, chief executives’ focus on and public discussion of these topics should be rising inexorably. Carbon emissions should be mentioned on 100 per cent of these earnings calls, some would argue.

But the data does challenge the idea that corporate attention to sustainability was a passing fad that’s now behind us. What has clearly passed is a peak of enthusiasm around low-substance green marketing efforts. Around 2021, some companies seemed to view climate pledges as a cheap, fashionable way of boosting their brands.

The subsequent backtracking on many of those pledges has been due, in some cases, to the haste and lack of rigour with which they were written. Another factor has been scrutiny of standards in the voluntary carbon market, which spooked some businesses that had viewed it as a cheap ticket to net zero status. The conservative political pressure in the US has given many companies further incentive to retreat from sustainability commitments.

But even those chief executives who prefer not to speak about carbon emissions on their earnings calls may find themselves forced to do so by analysts. The EU’s new carbon border tariffs, and new sustainability disclosure rules being imposed by securities regulators around the world, will make it increasingly hard for corporate leaders to dodge these subjects — even if Hollub’s New York incident might make them wish they could.

Smart read

Causing more than 50 deaths and tens of billions of dollars of expected losses, Hurricane Helene has highlighted the severe threat that climate change poses to the south-eastern US.

When one is working on investing into a system which has no ceiling, which does not produce the output which heavily outweighs the input, is it time to change direction? The real private sector has to make a profit and balance it's books, otherwise it would go out of business. The problem with a system which has no ceiling, one could continually increase salaries and throw money into a system which is ineffective, this could lead to a total breakdown of the economy of each and every country, especially if those running such a system, held the the power to ban anything they did not own, thus no competition, could lead to a system spiralling downward out of control, where an economy is not balanced, they may not have the funds set aside to help those who are dealing with or have been affected by an actual crisis ? When a system is put in place, where the economy is balanced, the output must outweigh the input, and the price must be an affordable price to all, thus ensuring that the public have sufficient funds for heat, light, food and a healthcare system built on helping to cure people, ensuring the system is moving on an upward path, so the funds are available to deal with an actual crisis.