“Dark Money”, by Ed Merta

We just need government, academia, and companies to work together to make sure people only get correct information.

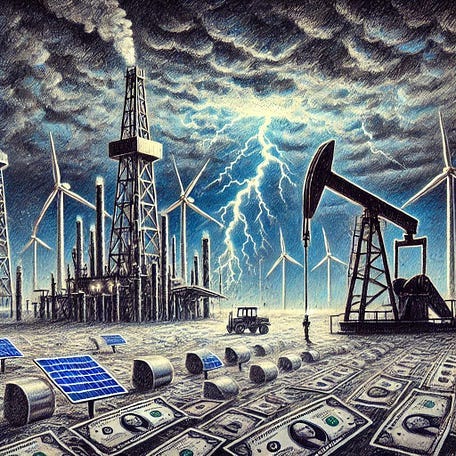

Dark money

So. We have one example of both sides actually doing it, where “it” means using government as a club to beat down local government and marketplace competitors. Do we have other examples of this sort of thing?

Turns out, as you might suspect, that we do. In an Ohio public hearing about whether the state should approve a local solar project, an opponent of the project admitted under oath to conversations with fossil fuel industry representatives about opposing the project. The article about this (see previous sentence) in the climate activist press implied that local residents oppose obviously beneficial solar and wind projects happens only, or mainly, because extremely wealthy and powerful fossil fuel companies use their influence to spread lies, hoping to squash a marketplace economic competitor. Without that malign intervention, local obstruction to wind and solar development would not be nearly as pervasive or effective. If people don’t hear the ideas of the bad people, they will think correctly

. We just need government, academia, and companies to work together to make sure people only get correct information.

Similar conclusions follow from a recent comprehensive study of the influence of fossil fuel companies on universities and academic research in developed countries. One of the study’s authors commented to climate activist media that oil, gas, and coal companies have infiltrated their tendrils of money, influence, and sympathy across thousands of university administrative offices, research departments, and scholarly publications. Universities, according to the study authors, must purge this systemic, almost spiritual infiltration from their institutional bodies and minds. Colonization and seduction by fossil energy thought, the study cautions, doesn’t turn universities into bastions of climate denial or even political conservatism. More insidiously, it promotes unthinking acceptance of “discourses of climate delay.” It subtly becomes permissive toward bad thinking, favorably inclined toward “narratives that push non-transformative solutions.” Promoting the wrong kind of innovation is one such appealing-sounding but predatory practice.

University researchers who investigate carbon capture and storage fall into the category of harmful innovation, the paper charges. The paper warns against legitimizing such research, because it promotes the toxic narratives of “Fossil Fuel Solutionism and Technological Optimism” [capitalization in original]. This innovation is toxic because it promotes “economically or technologically unproven technologies, such as carbon capture and storage.” We can’t have research to investigate things that aren’t proven yet. Such research into the unproven, by faculty with ties to fossil fuel companies, “can be weaponized to greenwash a company’s public image, contributing to…the industry’s ‘Fossil Fuel Savior’ framing of the climate crisis.”

To guard against contamination of the university, the paper urges exposing the presence of pro-fossil fuel individuals on campuses. “[F]ossil fuel companies have embedded themselves in universities across the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia, and beyond. They and their representatives fund research, sit on governing boards, host recruitment events, advise curricula, and more[.]” These people must be rooted out, like tumors. Good researchers must expose the infiltration. They “have an opportunity to go further than research: to communicate their findings widely, to advocate for the policy implications of their work, and to support others in doing so[.]” The paper quotes an activist faculty member on this imperative: “[A]s climate scholars, it is our professional responsibility to engage in climate politics and use our expertise to serve as advocates, to identify the political causes of climate inaction as well as solutions to overcome them.”

This means exposing faculty, administrators, or board members who take money from fossil fuel companies, as Harvard students have doneto fossil fuel-connected individuals on the university’s governing board, in its law school, and in its school of public policy. Similarly, Brown University has pledged “to halt collaboration with individuals and organizations involved in science disinformation, following faculty criticism of donations from the Charles Koch Foundation, which promotes climate change denial.” Ultimately, countering denial means identifying subversive individuals and removing them from campus. It’s the only way to stop “a conspiracy so immense and an infamy so black as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man.”

To people on the left, this all sounds great. Expose the Koch Brothers and kick their stooges off campus? Yeah, why not, right? Because it’s a recipe for an endless cycle of retaliatory witch hunts, that’s why. The green energy industry and its money also sit on university boards, in administrative suites, in faculty offices. They now enjoy historically massive federal subsidies and political power, alleviating a long-standing disparity with fossil industries. Should that be the occasion for antagonistic energy activists on campus to shame and harass each other in an endless cycle of paranoia? Is that a recipe for a productive, functional university?

Or society?

The same concern applies to clashes over the green energy transition in rural America. Undoubtedly, fossil fuel companies would better serve their own interests by advocating openly in rural forums, instead of trying to pull off bumbling, behind-the-curtain shenanigans for environmental media to gloat over with “gotcha” articles. Does it follow that an endless cycle of hunting down local conspirators accused of collaboration with dark, predatory forces is a good way to build community relationships? Or a reliable, affordable energy supply? Or do anything about your favorite problem besides get people addicted to rage and fear?