HEADLINE: “Scientists say they can calculate the cost of oil giants’ role in global warming”, By Nicolás Rivero

“Climate advocates hope this sort of model could result in court rulings that make polluters pay. The oil and gas industry contests the science.”

Scientists say they can calculate the cost of oil giants’ role in global warming

Climate advocates hope this sort of model could result in court rulings that make polluters pay. The oil and gas industry contests the science.

The Pemex Deer Park oil refinery is seen April 8 in Deer Park, Texas. (Ronaldo Schemidt/AFP/Getty Images)

By Nicolás Rivero

Oil and gas companies are facing hundreds of lawsuits around the world testing whether they can be held responsible for their role in causing climate change. Now, two scientists say they’ve built a tool that can calculate how much damage each company’s planet-warming pollution has caused — and how much money they could be forced to pay if they’re successfully sued.

Collectively, greenhouse emissions from 111 fossil fuel companies caused the world $28 trillion in damage from extreme heat from 1991 to 2020, according to a paper published Wednesday in Nature.

Industry officials have contested this sort of reasoning, and Trump administration officials, along with some congressional Republicans, are working to shield oil and gas companies from legal liability for climate-related damages.

The new analysis could fuel an emerging legal fight. The authors, Dartmouth associate professor Justin Mankin and Chris Callahan, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University, say their model can determine a specific company’s share of responsibility over any time period.

“There’s long been this veil of plausible deniability that any emitter could hide behind: ‘We’re all emitting greenhouse gases, so who’s to say that mine are the ones responsible for outcome X, Y or Z?’” Mankin said. “We can now do that accounting exercise.”

Many climate advocates have hoped that establishing blame in a way that can be submitted into evidence could result in court rulings that make polluters pay. And outside researchers say this model goes further than anything that has come before it in connecting company actions to concrete harm.

“This is the first time I’ve seen this done in a really comprehensive way that isn’t just for one specific event,” said Kevin Reed, a professor at Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences. “This is the real deal.”

Mankin and Callahan focused on harm from extreme heat that would be reflected in economic growth figures, including crop losses and lower worker productivity. Their model would need further adaptation before it could be applied to cases that make claims about other sorts of damage or more specific harms — such as the lawsuit filed by Multnomah County, Oregon, which seeks to hold 17 oil and gas companies accountable for a 2021 heat wave associated with the deaths of 69 local residents.

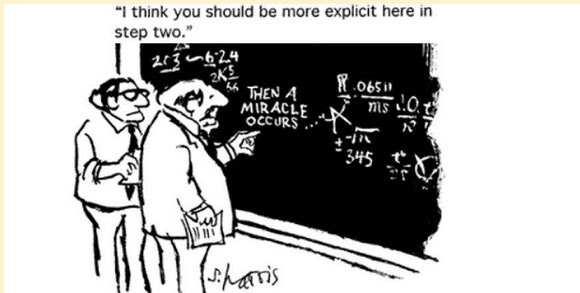

But some legal scholars say introducing this sort of calculation into a courtroom could devolve into a “battle of the experts,” with each side hiring scientists to run different models with different assumptions to reach conflicting conclusions about a company’s share of responsibility for climate change and its harms.

The American Petroleum Institute, which represents the oil and gas industry, defended its operations when asked about the Nature paper.

“The record of the past two decades demonstrates that the industry has achieved its goal of providing affordable, reliable energy, while improving standards of living globally and reducing emissions,” API spokesperson Bethany Williams wrote in an email.

“Retroactively penalizing U.S. oil and natural gas producers for delivering the energy consumers need is unconstitutional, and we welcome the administration’s efforts to address this state overreach.”

The evolution of climate ‘attribution science’

Callahan and Mankin’s model is built on decades of work in the field of “attribution science,” which tries to explain how much greenhouse gas pollution has changed Earth’s climate and contributed to particular disasters, such as heat waves and floods.

Scientists published the first landmark event attribution study in 2004, which showed that a record-breaking European heat wave that killed tens of thousands of people the previous year was twice as likely because of climate change.

Since then, researchers have published hundreds of studies showing how climate change raised the risk or multiplied the damage of particular disasters — some of which would have been nearly impossible without the planet-warming pollution people have created. They’ve also built more powerful models to calculate the financial damage from these disasters and developed models that show how much particular polluters’ greenhouse emissions have contributed to changing Earth’s climate.

Meanwhile, researchers have built a public database tracking decades of greenhouse emissions from 180 of the world’s biggest oil, gas, coal and cement companies. The database uses companies’ annual reports, Securities and Exchange Commission filings and other self-reported data, along with third-party estimates from sources such as the U.S. Energy Information Administration, to calculate production and emissions.

Callahan and Mankin’s work combines all of these steps — estimating a company’s historical emissions, figuring out how much those emissions contributed to climate change and calculating how much economic damage climate change has caused — into one “end-to-end” model that links one polluter’s emissions to a dollar amount of economic damage from extreme heat.

By their calculation, Saudi Aramco is on the hook for $2.05 trillion in economic losses from extreme heat from 1991 to 2020. Russia’s Gazprom is responsible for $2 trillion, Chevron for $1.98 trillion, ExxonMobil for $1.91 trillion and BP for $1.45 trillion.

Industry groups and companies tend to object to the methodologies of attribution science.

“This baseless ‘perspective’ piece ignores the scientific impossibility of attributing particular climate and weather events to any specific country, company, or energy user,” Theodore J. Boutrous, a lawyer for Chevron, wrote in a statement. “This so-called ‘attribution science’ is junk science. It is part of a misleading advocacy campaign on behalf of wasteful and unconstitutional state lawsuits and energy penalty laws.”

Companies like Chevron could seek to contest the assumptions that went into each step of Mankin and Callahan’s model.

Indeed, every step in that process introduces some room for error, and stringing together all of those steps compounds the uncertainty in the model, according to Delta Merner, lead scientist at the Science Hub for Climate Litigation, which connects scientists and lawyers bringing climate lawsuits. She also mentioned that the researchers relied on a commonly used but simplified climate model known as the Finite Amplitude Impulse Response (FAIR) model.

“It is robust for the purpose of what the study is doing,” Merner said, “but these models do make assumptions about climate sensitivity, about carbon cycle behavior, energy balance, and all of the simplifications in there do introduce some uncertainty.”

The exact dollar figures in the paper aren’t intended as gospel. But outside scientists said Mankin and Callahan use well-established, peer-reviewed datasets and climate models for every step in their process, and they are transparent about the uncertainty in the numbers.

Applying attribution models to legal arguments

Many of the climate lawsuits making their way through courts around the world involve questions of attribution.

One of the furthest along globally is the case of a Peruvian farmer who alleges that German energy company RWE’s greenhouse gas emissions warmed the planet and sped the melting of a glacier, which threatens to flood his Andean home. Hearings started last month, and, if the case results in a ruling or settlement, it could set a major precedent in Germany.

But legal experts say the most significant climate lawsuits could play out in the United States, because the American legal system is particularly friendly to plaintiffs suing for massive damages — and generally doesn’t force losing plaintiffs to pay the other side’s legal fees, which makes it less risky to try out novel legal arguments.

“The U.S. has a longer history of very large tort damages, where hundreds of millions of dollars have been awarded in damages in various cases,” said Michael Gerrard, who founded Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. “Most other countries don’t have that tradition.”

President Donald Trump has directed the Justice Department to weigh in on climate lawsuits by filing briefs aligned with the defendants, and fossil fuel companies have asked members of Congress to pass a law making them immune from climate lawsuits. That’s unlikely to happen, because Democrats in the Senate can block the effort with a filibuster, Gerrard said.

American climate cases tend to be modeled after the landmark U.S. tobacco and opioid lawsuits, which successfully argued that companies knowingly deceived the public about the harms of their products. The eventual settlements forced companies to pay billions in damages and fund public education campaigns.

Similarly, Massachusetts and Honolulu are each suing fossil fuel companies for misleading the public about their contributions to climate change. The Massachusetts case could go to trial in the next year or two, according to Corey Riday-White, a managing attorney at the Center for Climate Integrity, a nonprofit that supports climate deception lawsuits against fossil fuel companies.

“These lawsuits have not been held up by a lack of scientific evidence so far,” said Benjamin Franta, who heads the Climate Litigation Lab at the University of Oxford. Rather, most of the proceedings have focused on legal questions, such as jurisdiction.

“But some of the cases are getting close to trial now,” he said. “And, at that point, it will be important to show that these companies actually are responsible for damages in a particular state, city or county.”

Mankin and Callahan said their model is designed to be affordable, easy to run and adaptable to a range of scenarios, which they hope will make it a useful tool for anyone trying to hold companies accountable for climate pollution.

In addition to potentially supporting lawsuits, models like this could help enforce laws that make companies pay for the consequences of their greenhouse gas emissions. New York and Vermont recently passed those sorts of laws, and California and Maryland are considering similar versions.

Trump’s April 8 executive order accepted industry arguments that such laws and the climate lawsuits amount to overreach that hampers the energy sector and burdens consumers. “These State laws and policies weaken our national security and devastate Americans by driving up energy costs for families coast-to-coast,” he wrote, adding: “They should not stand.”

BOTTOMLINE: 99.9% of lawyers give their profession a bad name.” Steven Wright

Biggest bunch of bull.

“ climate change” it’s just a catch all really it’s a black hole an excuse for everything